The Metaphysics of Money: A Decisive and Satisfactory Explanation of

What Money Is

Cautionary prolegomenon

to this exemplar of fine-grained analytic-philosophical analysis:

Pay careful attention to my typography. When I am mentioning (the word) “money”, I use inverted commas in

the fashion you just observed. When I am talking about money – ‘referring’ to

the ‘thing’ – I eschew inverted commas in the fashion you just observed. When I

am talking about the ‘concept’ MONEY, I use CAPS à la Fodor. Finally, when I am

using unforgiveably vague and unhelpful but irreplaceable words, I nest these

words in single inverted commas, in the fashion you have observed throughout this

cautionary prolegomenon in the case of the words “refer”, “thing” and “concept”.[1]

The question ‘What is money?’ is a difficult one, to be sure.

Money is not a ‘physical’ thing (a thing exhaustively characterised by its

‘physical’ properties (that is, physical [in narrow sense] and chemical

properties or secondary qualities (and under label “secondary qualities” I

comprehend all macroscopic (perceptible by Homo sapiens without aid of

instruments), ‘commonsense’ properties of entirely non-symbolic (so-called

‘mind-independent’) kind (colour, size, texture, smell, taste, mass, etc)).

That is why the question ‘What is money?’ is not like the questions ‘What is

gold?’, ‘What is water?’, ‘What is sand?’, ‘What is alcohol?’, ‘What are

clouds?’, ‘What is polyester?’, ‘What is limestone?’, ‘What is steel?’, ‘What

is water?’, ‘What are stars?’, ‘What is hydrochloric acid?’, and so on. These

are all words which can be satisfactorily defined without any reference to the uses

to which we or other animals put the referents of these words (that is,

according to the functions of these

things), merely according to the ‘physical’ properties of the things (in the

very, very wide sense of ‘physical’) (although a dictionary definition would

typically mention the functions or uses of at least some of these objects too).

The question ‘What is money?’ is also not a ‘taxonomic question’ like the

questions ‘What is a tree?’, ‘What are mushrooms?’, ‘What is lettuce?’, ‘What

are tomatoes?’, ‘What are dolphins?’, ‘What is a chimpanzee?’, ‘What are

starfish?’, ‘What is socialism?’, ‘What is capitalism?’, ‘What is football?’.

These are all questions which no sane person would try to answer in terms of ‘physical

properties’, but by the introduction of the overarching categories in which

these things fit: ‘X is a type of Y with these unique properties distinguishing

it from other Y things’.

“Money” also does not fall into

the definitional category that probably the majority of words for everyday,

household objects falls into: that of being best defined according to both

function/functions and average ‘physical’

properties. “TV”, “DVD”, “chair”, “door”, “doorknob”, “washing machine”, “car”,

“bin”, “knife”, “fork”, “spoon”, “soccer ball”, “tennis racquet”, “spade”, “broom”

and “lawnmower” are all words whose referents cannot be defined purely according to their function,

independent of physical manifestation, but which instead need to be defined

according to function plus common physical properties. For example, chairs have

the function of seats – namely, providing people a resting place in a specific

posture – but, at the same time, they are not exhaustively characterised by

this function: in order to be distinguish “chair” from “seat” and “stool” and “sofa”,

a good definition will mention typical ‘physical’ feature of chairs which make

chairs chairs and not seats, stools or sofas. Notably, the Google definition

does this: “A separate seat for one person, typically with a back and four

legs.”

So is “money” such an unusual

word that we literally have no semantic category into which it can be placed?

The answer to this question is “No”. “Money” falls into the relatively rare category

of “Word for type of thing (/highly multiply realisable thing) which is exhaustively

characterised by its function/s )”. Analogous words are “computer”,

“engine”, “shop” or “weapon”; these

are all types of things which (I believe) can be defined satisfactorily purely

by function. “Computer” can be defined as any ‘thing’ (any ‘machine’ or ‘natural

system’ (in broadest possible sense)) which performs the same functions as Turing

machines (and the Turing machine is, of course, a specific imaginary object

with formally specified properties). This definition eliminates any ambiguity (in

situations of full knowledge) over what counts as a computer and what does not.

“Engine” can be defined as “any machine which converts power into motion”. “Shop”

can be defined as “a building or part of a building where goods and services

are sold” (and “building” is such a general notion that, from this definition

alone, you would (rightly) have no sense what shops look like (shops can be

mere “stands”, after all, or can be set up inside stationary vehicles)). And,

lastly, “Weapon” can be defined as “a thing designed or used for inflicting

bodily harm or physical damage”.

It should be noted, of course,

that “money” cannot be defined as neatly as these other ‘things’; “money” is

used to refer to too many different ‘things’ to have a straightforward,

sufficient-and-necessary-conditions-providing definition like those of the

above. MONEY is somewhat more of a ‘family resemblance concept’ (as much as I

dislike the word “concept”).

Before I give the standard

account of the “functions” of money (along with my extensive annotations), I

will draw up a two-part list of things we might call ‘money’, roughly in order

of most money-like to least money-like. When we do give the standard account of

the functions of money, this two-part list will allow us to see which things

the standard account would classify as most essentially money. We’ll do this list in two parts. The first part will be the

list of money-things that are included in the official measures of the “money

supply” and which make up, the second part will be other things we might call “money”

which do not fall under official measures.

Part I

· Tangible

currency: coins, ‘paper’

·

Demand deposits/fractional reserve current

accounts

·

Traveller’s cheques

·

Savings accounts

·

Time deposits under $100,000

·

Larger time deposits and similar institutional

accounts

Part II (misc.)

· ·

“Semi-primitive currencies” – that is, commodity

currencies in use in chiefdoms or state societies which are too valuable in

themselves to be used extensively for barter and/or degrade such that they are

not useful stores of value. As we will see, I am using this label to refer to either commodity currencies with high use-value given by citizens to a state as

a form of tax (as occurred in ancient Sumer, and presumably most chiefdoms), or precious-metal commodity

currencies made by a state which are too valuable in themselves to become

widely used as a currency for barter and trade by the masses (à la ancient

Sumer (with silver bars used as currency by the elites) and Rome and early-capitalist

Europe (with precious-metal coins never used as the main currency for barter and trade by citizens (despite what some

think)). In ancient Sumer, the basic monetary unit was the silver shekel, which

had fixed exchange rates in terms of barley: “One shekel’s weight in silver was

established as the equivalent of one gur, or bushel of barley. A shekel was

subdivide into 60 minas, corresponding to one portion of barley – on the

principle that there were 30 days in a month, and Temple workers received two

rations of barley every day” [Graeber, 2011: 39]. Temple bureaucrats apparently used the

system to calculate the people’s debts (rents, fees, loans, etc) in silver.

This means that “Silver was, effectively, money” [39]. The peasants who owed

money to the Temple or Palace, or to some Temple or Palace official, seem to

have settled their debts mostly in barley, which explains the importance of

fixing the exchange rate. Various other valuable commodities – “Goats,

furniture or lapis lazuli” – seem also to have been perfectly acceptable, since

the Temples and Palaces could find uses for most things [39]. I would classify

all these forms of commodity money as “semi-primitive currencies”.

Coins made

primarily of precious metals have never historically been widely used as the

dominant currency for barter and trade between citizens, and can thus be almost

universally regarded as “semi-primitive currencies”. L. Randall Wray explains [http://neweconomicperspectives.org/2011/08/mmp-blog-12-commodity-money-coins.html]:

“The first coins were created thousands of years [after the Sumerian empire],

in the greater Greek region (so far as we know, in Lydia in the 7th century

BC). And in spite of all that has been written about coins, they have rarely

been more than a very small proportion of the “money things” involved in

finance and debt payment. For most of European history, for example, tally

sticks, bills of exchange, and “bar tabs” (again, the reference to “wiping the

slate clean” is revealing—something that might not be done for a year or two at

the pub, where the alewife kept the accounts) did most of that work.

Indeed, until

very recent times, most payments made to the Crown in England were in the form

of tally sticks (the King’s own IOU, recorded in the form of notches in

hazelwood)—whose use was only discontinued well into the 19th century (with a

catastrophic result: the Exchequer had them thrown into the stoves with such

zest that Parliament was burnt to the ground by those devilish tax collectors!)

In most realms, the quantity of coin was so small that it could be (and was)

frequently called in to be melted for re-coinage.” Wray explains in the next

instalment of his serialised book that the story was slightly different in the

case of Ancient Rome, where there was a wider distribution of coinage – but

it’s certainly not the case that

common people, far away from Rome, would typically be bartering in coins

consisting of precious metals.

·

“Local non-primitive currencies” – that is, merely

instrumentally available, easily producible currencies like tally sticks or bar

tabs which can potentially be distributed throughout a small community (eg A

gives B an IOU token in exchange for goods and C accepts this token from B in

exchange for goods because C thinks she can redeem the token from A, and so on),

but which could never become proper currencies for societies as a whole because

they are potentially producible by all (the notion of money growing on trees is,

of course, a literal paradox; if money grew on trees, we couldn’t use it as

money (unless those trees only occurred in the king’s garden or whatever)).

·

“Primitive currencies” – that is, currencies

which have high use-value or aesthetic-value in themselves, used to arrange

marriages (as dowries) or to settle disputes (not to buy and sell commodities), in hunter-gatherer or

hunter-horticultural societies. Examples are cattle in eastern or southern

Africa, shell money practically everywhere [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Shell_money]

[Graeber, 2011: 60].

·

“Cryptocurrencies” [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cryptocurrency]

like Bitcoin

·

Promissory notes

·

Bank cheques

·

Government securities/bonds (have been used as

money, eg: http://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/africa/zimbabwe-bond-notes-harare-protests-new-currency-dollar-mugabe-crisis-a7447956.html, and apparently traders are known to call short-term bonds "cash")

Now onto the functional account

of money.

The standard modern textbook account

of the nature of money (and there is one, which I will give in a minute) originally

derives from William Jevons’ account in Money

and the Mechanism of Exchange [1875]. Jevons claimed that money can be

understood in terms of the following four functions: it is a “medium of exchange”, a “common measure of value” (nowadays

translated to “unit of account”), a “standard of value” (nowadays translated to “standard of

deferred payment”), and a “store

of value”. I think Jevons

probably thought that x is money iff

it plays these four roles – in other words, that these functions give the

sufficient and necessary conditions (this would have been accurate in his

specific context, I believe, if he was only thinking about the official

currency in 19th Century England, which would have been the

exclusive player of all these roles). The standard textbook account of the

nature of money compresses Jevons’ account to a triptych. Money, it is said,

acts as the following:

1.)

A medium of exchange

2.)

A unit of account (measure of value)

3.)

A store of value

I will now explain these in more

detail.

1.)

A medium of exchange means any abundant (but not easily obtainable or producible, except perhaps by some central authority) ‘thing’ used to compare the ‘value’ of dissimilar objects; this, of course, implies

that this ‘thing’ itself has a fixed value agreed upon by a community

or society. The fact that money performs this role in our societies is why,

even absent trust and a feeling of obligation between two trading partners

in our modern societies (absent one partner’s willingness to credit herself

against the other in knowledge that the other will seek to repay her

eventually) there is no necessity of ‘coincidence of wants’. Without any kind

of medium of exchange, there are very few circumstances under which two strangers

or non-kin acquaintances will be happy to exchange anything at all (unless

there is a dispute to settle or a marriage to arrange, in which case there

might be a gift exchange (or a one-sided gift transfer)). Without a medium of

exchange, if two strangers have minimal trust in each other and/or won’t see

each other again (such that neither party would be willing to credit herself

against the other) and/or have no reason to gift one another, these strangers will

fail to complete a transaction unless there is a ‘coincidence of wants’: unless

person A desires to acquire something of B’s that B is willing to give away for

things that A has on hand (or vice versa). The ‘endowment effect’ [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Endowment_effect]

makes the actualisation of this kind of coincidence of wants extra unlikely (we

tend to develop strong attachment to objects which we have had in our

possession for a long time). But with some medium of exchange, B may well be

induced to give up the object A desires even if A doesn’t have anything that B

desires to acquire other than an

appropriate quantity of the thing acting as the medium of exchange. B will

take possession of an appropriate quantity of the thing because B knows that merchants

C and D will accept this thing in exchange for their wares, and merchants C and

D do this because they know that A, E, F and G will, and so on. Except in the case of “semi-primitive

currencies” or “primitive currencies”, this thing, in its physical form, necessarily

has, more or less, only instrumental utility. And why? Because these tokens can

be exchanged for any other commodity in future with any other person who

recognises money’s ‘value’.

2.)

Money’s function as a unit of account is what

makes commerce possible. As Wikipedia notes, “it is necessary for the

formulation of commercial agreements that involve debt”. But it also has a

profound consequence for our sense of morality, since once you live in a world

with money acting as unit of account, every commodity becomes potentially quantifiable,

because it becomes precisely monetisable, and even humans become potential

commodities. Money is an unstoppable desecrating force, making the unthinkable

thinkable, destroying taboos – indeed, making slavery possible. It inevitably

encourages a self-interested view of the world, because one starts thinking of

one as having precise debts to specific people and precise credits to specific

people, rather than as having an unpayable debt to one’s community.

Incidentally, Graeber argues that primitive currencies often didn’t act as a

unit of account, or measure of value. Dowry payments using primitive currencies

were typically given as a token, an acknowledgement, of an unpayable debt, the loss of a daughter.

3.)

What it means to say that money functions as a “store

of value” is that money can be reliably saved, stored and retrieved. This is crucial

for any complex economy, and when money stops acting as a store of value, you

get disaster (hyperinflation).

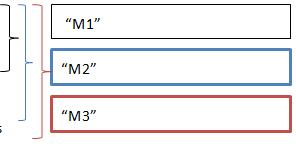

Now that that’s all done, it

should be clear why I claimed that MONEY is somewhat fuzzier than a concept

like WEAPON. My “M1” money-things fulfil all the functions, and thus the account

is perfect for those, but the other money-things in Part I of the list don’t

really fulfil the three functions. Savings accounts money is, by definition,

not acting as a medium of exchange. Once you get to Part II of the list, all

the money-items fail to fulfil at least one of the functions in the standard account.

That’s why it would be erroneous to say that this account gives the sufficient

and necessary conditions for a thing to be classified as money.

The really interesting thing,

though, is that – much as we can understand the concept of SHOP in terms of the

broader concept of the SOCIAL INSTITUTION or the concept of WEAPON in terms of

the broader concept of the TOOL – we can usefully analyse (in different ways) almost all the money-things in my

two-part list in terms of the much broader moral concept of DEBT. Although money is used to calculate debts, and we use money to pay off debts, all money (except perhaps cryptocurrencies and the semi-primitive currencies of the Sumerian-peasant-type, as I'll briefly note) can be understood also as a form of debt. I already explained how what I called "local non-primitive currencies" are always IOU tokens, but even general non-primitive currencies can be understood as a kind of IOU token - this time, the government's. A banknote can be seen as a kind of IOU token extended by the government, but one that the citizen-possessor can never redeem for anything, because what the government owes is precisely the IOU token itself (the IOU token refers to itself)! What matters is the fact that the government is guaranteeing the value of this IOU token precisely because it is the monopoly producer of IOU tokens. Once you adopt this analysis of the nature of government money, it makes perfect sense that we talk about government spending over taxation as the government falling into 'deficit': it is making lots of tokens signifying its debt and thereby going into debt, while putting others into credit by giving them these tokens. The government "pays off its debt" only by destroying some of these tokens through the tax system (this happens in modern, well-functioning capitalist economies simply by deletion of the digital version of these tokens from people's bank accounts, rather than by actually burning banknotes or whatever). In effect, the government "pays off its debt" by destroying the existence of the debt itself. What secures the value of the goverment's IOU tokens is the tax system. Fiat money proves, of course, that money becomes valuable to all chiefly because we all collectively perceive that it is valuable, because we all have common knowledge of its value (I know that you will accept it and you know that I will accept and I know that you know this and you know that I know this and I know that you know that I know, etc). Nevertheless, the fact that we are all legally required to relinquish some of it to the government at regular intervals helps underwrite that value by enforcing a kind of scarcity.

Thus a great deal of the money in Part I of my list - all of physical currency - can be understood as, in its origin, government debt. It is, of course, worth emphasising that not all the money in existence in the modern economy is government money. The private sector money surplus for any given year is highly affected by the government deficit, and, when the government "pays off its debt", what that means - as I said - is that it destroys money (a surplus means collecting more money in taxes than is spent). But it would be wrong to say that the private sector money surplus for any given year is determined by the government deficit. The MMTheorists go astray in making the equivalence statement “Private sector surplus = amount of government deficit + trade surplus”, because, as Steve Roth points out [http://www.asymptosis.com/where-mmt-gets-its-accounting-wrong-and-right.html], “The two primary sources of private assets (hence saving) are:

Thus a great deal of the money in Part I of my list - all of physical currency - can be understood as, in its origin, government debt. It is, of course, worth emphasising that not all the money in existence in the modern economy is government money. The private sector money surplus for any given year is highly affected by the government deficit, and, when the government "pays off its debt", what that means - as I said - is that it destroys money (a surplus means collecting more money in taxes than is spent). But it would be wrong to say that the private sector money surplus for any given year is determined by the government deficit. The MMTheorists go astray in making the equivalence statement “Private sector surplus = amount of government deficit + trade surplus”, because, as Steve Roth points out [http://www.asymptosis.com/where-mmt-gets-its-accounting-wrong-and-right.html], “The two primary sources of private assets (hence saving) are:

- Surplus

from production (how “surplus” is commonly used in the national

accounts), monetized by the markets for newly produced goods and services.

- Revaluation

of existing assets — assets produced in previous periods

— realized in the existing-asset markets.”

Nevertheless, the point stands

that all of our physical currency and a nontrivial amount of the virtual money

in banks can be understood as originated as a form of government

debt. To be clear, when I say this, I am not making any kind of high-falutin metaphysical claim; I am certainly not saying that government-created money equals government debt, which would imply that money is the only kind of debt a government can have (a very odd claim). I merely mean to say that that's one useful way in which you can analyse the nature of money generated by the government, and it directly jibes with the fact that we call the excess of spending over taxation in a given year a 'government deficit' and that this excess of spending over taxation helps create 'private surplus'. Obviously, the 'money as debt' analysis doesn't work when you adopt the perspective of a person with money going into a shop looking to purchase an item; money, for them, is, of course, the opposite of debt, namely, credit with zero interest (but then that's the whole point - money is like a magical asset that the government gives up to the public so that the public can be in credit).

As the not-for-profit

organisation Positive Money explains in its mostly excellent Youtube videos,

and as the Bank of England explains in this paper [http://www.bankofengland.co.uk/publications/Documents/quarterlybulletin/2014/qb14q1prereleasemoneycreation.pdf],

and as Steve Keen has forever been banging on about, with his advocacy of

Monetary Circuit Theory [https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Monetary_circuit_theory],

the Theory of Endogenous Money is correct. This means that private banks

actually create “the majority of money in the modern economy” (see BoE paper). This

doesn’t mean that Roth should have added bank lending to his sources of private

assets above, because, as he himself explains in that very article, with the

brief discussion of double-entry bookkeeping, banks do not create savings, and

thus, in an accounting sense, do not create private assets. Nevertheless, once

banks have made a loan, for which they don’t need any deposit to back up

(contra conventional Banks-as-Intermediaries theories), they have created a

medium of exchange, a unit of account and a store of value. This money needs to

be paid back eventually, and, when it is, it is destroyed. But that doesn’t

mean it wasn’t money when it did exist. And this money that banks create is

effectively also bank debt (even

though it is both debt and credit in an accounting sense, because of

double-entry bookkeeping). (Steve Roth recently published an article on

Evonomics which brilliantly explains the nature of money in the modern world: https://evonomics.com/heck-money-printing-anyway/).

Apart from cryptocurrencies and peasant-owned commodity money like the Sumerian peasants' 'money' (barley, goats, lapis lazuli, furniture, etc, paid to rulers), the Part II money-things can be even more naturally understood in terms of the

concept of debt. The semi-primitive currencies of the precious-metal-coin form

(like the precious metal coins of Ancient Greece or Rome or Medieval Europe)

are the state’s debt, like our modern currencies. The primitive currencies represent unpayable debts; they're typically ways of expressing sympathy at the receiver's loss for which they (or the group they represent) are in some way culpable. If it's a dowry payment, they're using the primitive currency to acknowledge the grief of the parents who are losing the daughter, and if it's one tribe using the primitive currency to pay another after a dispute in which the tribe paying out maimed or killed a member of the tribe being paid, then they're using the 'money' to express their guilt and sorrow. Bank

cheques, once written, represent one person’s debt to another. Government

securities/bonds are a form of state debt again.

Cryptocurrencies can't be understood as a form of debt because no one person has to go into debt to a person or to the community to bring the digital tokens into existence; the process of creation of the currency is a decentralised system which works in a complicated way I don't fully understand. Peasant-owned commodity money like the Sumerian peasants' money can't be understood as IOU tokens; it's instead 'money' whose high use-value is a form of credit being used to pay off debts.

Cryptocurrencies can't be understood as a form of debt because no one person has to go into debt to a person or to the community to bring the digital tokens into existence; the process of creation of the currency is a decentralised system which works in a complicated way I don't fully understand. Peasant-owned commodity money like the Sumerian peasants' money can't be understood as IOU tokens; it's instead 'money' whose high use-value is a form of credit being used to pay off debts.

And that’s all folks.

[1] I

don’t believe in “concepts”, at least insofar as that word implies cohesion and

stability (which it does to me). I believe that Prototype Theory is right, and

that there is a fundamental fuzziness

behind most of our words. I have coined my own words for the many-branching

splatter of notions that lie behind most of our words; these neologisms are “Syntasm”

and “Dendression”.

No comments:

Post a Comment